The hidden cost of invalid indexes in Postgres (yes, even on Supabase/RDS/Neon)

When CREATE INDEX CONCURRENTLY or REINDEX INDEX CONCURRENTLY fails, Postgres leaves behind an invalid index. Many engineers assume these indexes are harmless placeholders waiting to be cleaned up. After all, the planner won't use them for queries, right?

Wrong. Invalid indexes are far from harmless. They continue to consume resources, generate I/O, block optimizations, and even cause lock contention — all while providing zero query performance benefit.

In this article, we'll demonstrate — with real evidence — the hidden costs of invalid indexes that every Postgres administrator should understand.

If you're on Supabase, Neon, RDS, or any managed Postgres — this still affects you:

- Invalid indexes consume CPU, memory, and disk I/O on every write — but provide zero query benefit

- They increase your cloud bill through extra WAL storage and replication traffic

- They can cause mysterious migration failures when you retry ("relation already exists")

- Fix: Find them with PostgresAI checkup (20+ checks and counting) or the query below, then drop with DROP INDEX CONCURRENTLY

Where invalid indexes come from

Invalid indexes typically appear after failed concurrent operations:

-- This might fail and leave an invalid index.

-- For example, if the table is large and there is a low statement_timeout.

create index concurrently idx_orders_created_at on orders(created_at);

-- Check for invalid indexes

select

indexrelid::regclass as index_name,

indisvalid as is_valid,

indisready as is_ready

from pg_index

where not indisvalid;

An index with indisvalid = false is marked invalid. Postgres documentation suggests dropping these indexes, but many teams leave them in place, assuming they're inert. Let's prove why that assumption is dangerous.

Test setup

For all demonstrations below, we use this simple setup:

drop table if exists test_invalid_idx cascade;

create table test_invalid_idx (

id bigserial primary key,

indexed_col int,

non_indexed_col text

) with (fillfactor = 50);

insert into test_invalid_idx (indexed_col, non_indexed_col)

select i, 'initial' from generate_series(1, 100) i;

-- Create index, then mark it invalid (simulating failed CREATE INDEX CONCURRENTLY)

-- Real failure leaves indisready = true, indisvalid = false

create index idx_test_indexed_col on test_invalid_idx(indexed_col);

update pg_index

set indisvalid = false, indisready = true

where indexrelid = 'idx_test_indexed_col'::regclass;

Now let's examine each hidden cost.

1. Maintained on every write

Invalid indexes are updated on every INSERT and UPDATE, just like valid indexes. Using pageinspect (a contrib module for low-level inspection of database pages) to count B-tree leaf items:

create extension if not exists pageinspect;

-- Before: 100 leaf items in the invalid index

select count(*) as leaf_items from bt_page_items('idx_test_indexed_col', 1);

leaf_items

------------

100

-- INSERT adds a new entry to the invalid index

insert into test_invalid_idx (indexed_col, non_indexed_col) values (999, 'new');

select count(*) as leaf_items from bt_page_items('idx_test_indexed_col', 1);

leaf_items

------------

101

-- UPDATE also adds a new entry (B-tree indexes don't update in place)

update test_invalid_idx set indexed_col = 888 where indexed_col = 999;

select count(*) as leaf_items from bt_page_items('idx_test_indexed_col', 1);

leaf_items

------------

102

Every write operation pays the I/O cost of maintaining an index that provides zero query benefit.

2. Processed by VACUUM and generate WAL

VACUUM scans invalid indexes, consuming autovacuum budget:

delete from test_invalid_idx where id > 50;

vacuum verbose test_invalid_idx;

INFO: vacuuming "public.test_invalid_idx"

index "idx_test_indexed_col": pages: 5 in total, 1 newly deleted

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ Invalid index was processed!

DML operations also generate WAL records for invalid indexes. Using pg_walinspect (available in Postgres 15+):

create extension if not exists pg_walinspect;

-- Capture LSN before and after an INSERT

select pg_current_wal_lsn() as start_lsn \gset

insert into test_invalid_idx (indexed_col, non_indexed_col) values (999, 'wal_test');

select pg_current_wal_lsn() as end_lsn \gset

-- Find WAL records for our invalid index

select resource_manager, record_type, block_ref

from pg_get_wal_records_info(:'start_lsn', :'end_lsn')

where block_ref like '%' || (

select relfilenode::text from pg_class

where relname = 'idx_test_indexed_col'

) || '%';

resource_manager | record_type | block_ref

------------------+-------------+----------------------------------

Btree | INSERT_LEAF | blkref #0: rel 1663/5/16957 ...

^^^^^ Invalid index!

This means increased WAL volume, more data replicated to standbys, and larger backups.

3. Block HOT updates

This is the most significant impact. Postgres Heap-Only Tuple (HOT) optimization (deep dive) allows updates to avoid modifying indexes when indexed columns don't change. Invalid indexes block HOT on their columns — exactly like valid indexes would — but provide zero query benefit in return. You're paying the full cost of indexing with none of the upside. For more on how indexes affect update performance, see How partial and covering indexes affect UPDATE performance in Postgres and HOT updates and write amplification.

select pg_stat_reset();

-- Update non-indexed column

update test_invalid_idx set non_indexed_col = 'updated' where id <= 10;

select round(100.0 * n_tup_hot_upd / n_tup_upd, 1) as hot_percent

from pg_stat_user_tables where relname = 'test_invalid_idx';

-- Result: 96.8%

select pg_stat_reset();

-- Update column covered by invalid index

update test_invalid_idx set indexed_col = indexed_col + 1 where id <= 10;

select round(100.0 * n_tup_hot_upd / n_tup_upd, 1) as hot_percent

from pg_stat_user_tables where relname = 'test_invalid_idx';

-- Result: 0%

| Column updated | HOT % |

|---|---|

| Non-indexed | 96.8% |

| Covered by invalid index | 0% |

Zero HOT means more table bloat, more VACUUM work, degraded performance — all from an index that provides zero query benefit.

4. Pollute statistics

Invalid indexes show 0 scans in monitoring — they look like "unused indexes" unless you check indisvalid. A DBA running cleanup scripts might not realize the index is already broken.

5. Planner overhead and lock contention

During query planning, Postgres acquires AccessShareLock on all indexes for participating tables — including invalid ones (unless you use prepared statements):

begin;

explain select * from test_invalid_idx where indexed_col = 500;

select c.relname, l.mode from pg_locks l

join pg_class c on l.relation = c.oid

where l.pid = pg_backend_pid();

object_name | lock_mode

----------------------+-----------------

idx_test_indexed_col | AccessShareLock <-- Invalid index is locked!

test_invalid_idx | AccessShareLock

This conflicts with AccessExclusiveLock required by DROP INDEX, REINDEX, and ALTER INDEX. In a busy system, this can make it surprisingly difficult to drop the invalid index during normal operations. You're paying the same locking cost as a useful index, for nothing.

6. Block migration retries

Invalid indexes can block schema migration retries. Consider this common scenario:

-- Migration attempt #1: fails due to statement_timeout or other issue

create index concurrently idx_orders_created_at on orders(created_at);

-- ERROR: canceling statement due to statement timeout

The failed CREATE INDEX CONCURRENTLY leaves behind an invalid index named idx_orders_created_at. When you retry the migration:

-- Migration attempt #2: blocked!

create index concurrently idx_orders_created_at on orders(created_at);

-- ERROR: relation "idx_orders_created_at" already exists

The retry fails because the index name is already taken by the invalid index. This is particularly problematic in CI/CD pipelines where migrations run automatically — the pipeline will keep failing until someone manually drops the invalid index.

The fix: drop the invalid index first, then retry:

drop index concurrently if exists idx_orders_created_at;

create index concurrently idx_orders_created_at on orders(created_at);

Summary

| Impact (same cost as valid index, zero benefit) | Evidence |

|---|---|

| Maintained on every write | leaf_items: 100 → 101 → 102 |

| VACUUM processes them | "idx_test_indexed_col: pages: 5, 1 newly deleted" |

| WAL records generated | Btree INSERT_LEAF for invalid index |

| HOT updates blocked | 96.8% → 0% when column is covered |

| Planner locks them | AccessShareLock blocks DDL |

| Block migration retries | "relation already exists" error |

Finding them

Run this query to find all invalid indexes in your database:

select

n.nspname as schema,

c.relname as index_name,

t.relname as table_name,

pg_size_pretty(pg_relation_size(c.oid)) as size,

i.indisvalid as is_valid,

i.indisready as is_ready

from pg_index i

join pg_class c on c.oid = i.indexrelid

join pg_class t on t.oid = i.indrelid

join pg_namespace n on n.oid = c.relnamespace

where not i.indisvalid

order by pg_relation_size(c.oid) desc;

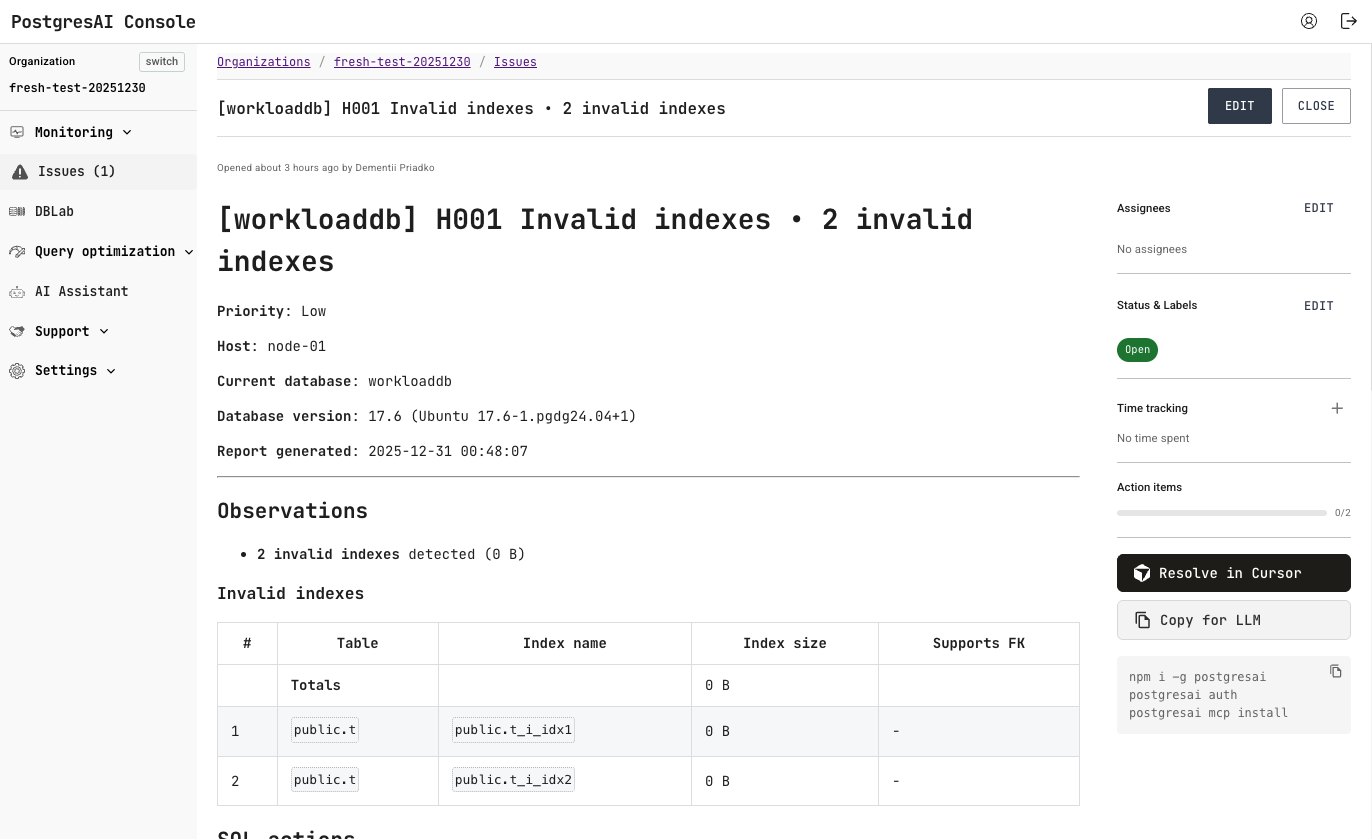

Or use PostgresAI to detect them automatically. This is one of our basic health check reports (H001) that helps teams clean up invalid indexes — either manually or fully automated with AI assistants like Claude Code or Cursor via the postgresai CLI/MCP:

Drop or recreate?

Before removing an invalid index, determine if it needs to be recreated. Here's how to decide:

1. Check for valid duplicates

If a valid index already exists on the same columns, just drop the invalid one:

select

n.nspname as schema,

ci.relname as invalid_index,

t.relname as table_name,

pg_get_indexdef(i.indexrelid) as definition,

-- Check for valid duplicate

(select string_agg(c2.relname, ', ')

from pg_index i2

join pg_class c2 on c2.oid = i2.indexrelid

where i2.indrelid = i.indrelid

and i2.indisvalid

and i2.indkey = i.indkey

) as valid_duplicates

from pg_index i

join pg_class ci on ci.oid = i.indexrelid

join pg_class t on t.oid = i.indrelid

join pg_namespace n on n.oid = ci.relnamespace

where not i.indisvalid;

2. Check if it backs a constraint

Indexes backing UNIQUE or PRIMARY KEY constraints must be recreated:

select

c.relname as index_name,

con.conname as constraint_name,

case con.contype

when 'p' then 'PRIMARY KEY'

when 'u' then 'UNIQUE'

end as constraint_type

from pg_index i

join pg_class c on c.oid = i.indexrelid

left join pg_constraint con on con.conindid = i.indexrelid

where not i.indisvalid

and con.conname is not null;

3. Check current query plans

See if queries are doing sequential scans that would benefit from the index:

-- Get the index definition

select pg_get_indexdef('your_invalid_index'::regclass);

-- Check query plan for typical queries on that column

explain select * from your_table where indexed_column = 'value';

-- Seq Scan on large table = probably need to recreate

Decision flowchart

╭───────────────────╮ ╔══════════════╗

│ Is valid index │───YES───►║ DROP INDEX ║

│ on same cols? │ ║ (Duplicate) ║

╰─────────┬─────────╯ ╚══════════════╝

│

NO

│

▼

╭───────────────────╮ ╔══════════════╗

│ Backs constraint? │───YES───►║ RECREATE ║

│ (UNIQUE/PK) │ ╚══════════════╝

╰─────────┬─────────╯

│

NO

│

▼

╭───────────────────╮ ╔══════════════╗

│ Table has │───YES───►║ DROP INDEX ║

│ < 10k rows? │ ║ (Monitor) ║

╰─────────┬─────────╯ ╚══════════════╝

│

NO

│

▼

╭───────────────────╮ ╔══════════════╗

│ Queries filter │───YES───►║ RECREATE ║

│ on this col? │ ╚══════════════╝

╰─────────┬─────────╯

│

NO

│

▼

╔════════════════╗

║ DROP INDEX ║

║ (Monitor) ║

╚════════════════╝

Note: always use DROP INDEX CONCURRENTLY and REINDEX INDEX CONCURRENTLY to avoid blocking other sessions.

What to do

Invalid indexes are not inert — they actively hurt performance. The next time you see one, don't postpone cleanup:

- Drop immediately with

DROP INDEX CONCURRENTLY(unless it backs a constraint you need) - Monitor — add

select count(*) from pg_index where not indisvalidto your alerts - Investigate — check Postgres logs to understand why the original

CREATE INDEX CONCURRENTLYfailed

Check your database for invalid indexes in 2 minutes — PostgresAI is free to start.